Alarming mental health statistics are being put in the too hard basket and quietly ignored, but the situation is getting worse.

This article is available as a PDF document.

Data covering 2021 released by Stats NZ showed a significant increase in the proportion of people with poor mental wellbeing, up from 22 percent in 2018 to 28 percent in 2021 across all age groups. Across the UK, rates of depression are significantly higher than prior to the pandemic. Around 17% of adults in the UK experienced some form of depression in summer 2021, compared to just 10% before the pandemic.

A report by Ipsos released in 2022 entitled “One in two New Zealanders reported having felt severely stressed and/or depressed in the past year” found:

“More than half of New Zealanders have felt stressed to the point where it had an impact on how they live their daily life (56%) and where they felt like they could not cope or deal with things (53%). One in four New Zealanders reported having seriously considered suicide or self-hurt in the last year.

“Three quarters of our young people (aged 18-34) have felt stressed to the point that has impacted on their daily life and made them feel unable to cope, with 40% saying that they have seriously considered suicide or self-harm in the last year.”

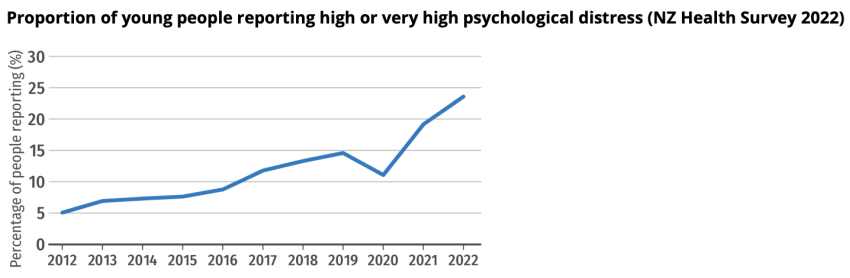

A report released by the NZ Salvation Army in 2023 entitled “State of the Nation 2023” found a sharp increase in the proportion of young people aged 15 to 24 suffering high levels of psychological distress, including anxiety, fatigue or depression. In just two years, the proportion has jumped from 11.1% in 2020 to 23.6% in 2022.

These figures give us a concerning snap shot which does not amount to a complete picture, but nevertheless, they confirm a mental health crisis.

Just 10% of people seek help for mental health issues. Most expect to struggle on and get through it without help. Yet, as the incidence and severity of Covid infection declines, mental health issues are not declining, the above figures show they are rapidly getting worse.

We tend to think of the causes of mental health issues in purely psychological terms. Our material circumstances including housing and finances, life events, emotional and physical traumas, relationships, stress levels, etc. are all cited as relevant factors. They do indeed greatly affect mental health outcomes. During the height of the pandemic social support mechanisms and organisations vital to well being were undermined by government policies which instituted lockdowns, mandates and the associated social isolation.

Because of the presumption of an overt cause, the increasing levels of mental ill health have not so far been associated with Covid vaccination. Yet psychological distress always has physiological counterparts. Mental health is profoundly affected by any drugs we take, the balance of our hormones, nutritional adequacy, and the health of our various organs and organ systems. Our genetic and epigenetic make up is also in play.

The healthy functioning of our whole physiological system is intimately involved with the balance of our mental health. Multiple published papers suggest that Covid-19 vaccination initially relieved anxiety and distress but only over the short term. In other words, people become less worried about the possible effects of Covid infection because they felt protected by the vaccine, but in contrast published data shows that mental health is declining rapidly over the longer term.

Presumably there is less worry today in general about Covid infection because Omicron is known to be mild and its incidence is declining. Lockdowns are also a thing of the past, largely confined to 2020 and the first half of 2021. We would not expect that mental ill health would continue to increase as a result of these factors to this extent, rather it should have begun to decrease by now.

Are financial pressures and worries causing a rapid decline in mental health? For comparison, studies have focused on the effect of the 2008 financial crisis on the US population which arguably had a greater financial impact than that currently being experienced post pandemic. Figure 1 in a 2019 paper entitled “The Great Recession and Mental Health in the United States”, shows that the long term impact of the recession on depression and anxiety among the whole population was minor and statistically insignificant.

It is true that incidence of mental health problems has been gradually increasing for years and this is possibly connected to deteriorating social conditions and rising poverty, but in 2021 there was a structural break in the time series evident in the following graph. Mental health problems rose sharply after 2020.

According to the NZ Health Survey mental health issues among young people in NZ were rising by 12.5% per year just prior to the pandemic, an alarming figure, but in 2021 this rose by a massive 33% and continued rising steeply in 2022. Depression among adults in the UK rose by 70% in 2021. The NZ Salvation Army report records depression, fatigue and anxiety growing by 113% over the two years 2020-2022. These rises are unprecedented.

So what has occurred to cause these increases?

The obvious candidates are Long Covid and Covid vaccination. Long Covid is estimated to affect 10% of those suffering acute Covid infection. A study of the effects of Long Covid in Korea entitled “Long COVID prevalence and impact on quality of life 2 years after acute COVID-19” found that among 132 people who suffered acute Covid infection early in the pandemic during the alpha variant dominant period, 94 experienced persistent symptoms including fatigue (35%), amnesia (30%), concentration difficulties (24%), insomnia (21%), and depression (20%). 43 participants were still experiencing some symptoms at 24 months.

All the subjects also received Covid vaccination subsequent to Covid infection and therefore in common with most studies of Long Covid any separate or confounding effects of Covid vaccination could not be adequately assessed.

Despite the symptoms noted in this study which are consistent with current poor mental health outcomes, its conclusions are limited to those who had acute infection with the more severe alpha variant. Its relevance to NZ, which largely escaped alpha and delta infections, is very limited. The low numbers of people suffering acute Covid infection render it somewhat unlikely that Long Covid is solely responsible for high rates of mental illness spread among the whole population.

Moreover, the inability of the authors to distinguish possible effects of Covid vaccination as opposed to Long Covid is a severe limitation of the Korean study. This limitation was rectified with the recent publication of another Korean study “Mental health and governmental response policy evaluation on COVID-19 based on vaccination status in Republic of Korea.” Crucially, this study found that vaccinated individuals were more likely to suffer from depression (characterised as Covid Blues) than the unvaccinated.

The authors do not comment on the causes of the greater mental health resilience of the unvaccinated or conversely on the mental health deficit of the vaccinated. However a conclusion is all but inescapable: mRNA Covid vaccination could adversely affect mental health.

Depression is characterised by persistent sadness and a lack of interest or pleasure in previously rewarding or enjoyable activities. It can also disturb sleep and appetite. Tiredness and poor concentration are common.

The mechanism by which mRNA Covid vaccination can affect mental health is unclear. Covid vaccines are designed to cross the cell membrane and redirect cellular processes to produce Covid spike protein. The spike protein has been shown to be toxic to cardiac function. Spike protein has been detected up to 6 months subsequent to vaccination. There is no current evidence suggesting that spike protein causes depression.

Genetic information is transferred from genomic DNA to messenger RNA to the three-dimensional proteins that affect physiological structure and function. It seems possible that the disruption of cellular function caused by mRNA vaccination might be connected to psychological effects. Neurons produce neurotransmitter proteins. In addition to regulating physiological processes, neurotransmitters also serve psychological purposes, including learning and controlling emotions like fear, pleasure, and happiness.

RNA plays a role in post-transcriptional modifications affecting ion channels and neurotransmitter receptors. These RNA processing events have been shown to be critical for the normal development and function of the nervous system. A paper published in 2018 entitled “Role of RNA modifications in brain and behavior” found that unlike the relatively stable genetic code, our combinatorial RNA epigenetic code if dynamically reprogrammed can be associated with psychiatric disorders.

It is important to realise that mental health is associated with the balanced functioning of huge networks of neuronal cells. Humans have over 37 trillion cells, each containing identical DNA. Wide scale disruptions of RNA mechanisms might affect cellular network properties. A 2016 study entitled “Neuronal networks in mental diseases and neuropathic pain: Beyond brain derived neurotrophic factor and collapsin response mediator proteins” reported:

“The brain is a complex network system that has the capacity to support emotion, thought, action, learning and memory, and is characterised by constant activity and constant structural remodelling….From this viewpoint, increasing experimental/clinical observations suggest that mental disorders are neural network disorders.”

In fact neural connectivity and neuroplasticity are at the heart of neural networks. The brain is not a static network, it responds to experience, changing in structure and function, often by a great deal. As we saw above, neural connectivity is mediated by RNA activity. If this is disrupted by mRNA vaccines, it is entirely possible that mental health could be affected. In particular, well being and the functional aspects of decision making could be affected as happens in depressive states.

The foregoing discussion is extremely important. We need access to up-to-date stats on mental health to ascertain the extent and causes of the current problem. Given what was already known pre-pandemic about the interdependence of mental health and genetic and epigenetic processes, it should have been recognised that mRNA vaccines had potential psychiatric implications. The fact that this was not recognised or discussed is a deficiency of regulatory processes. The failure to communicate this risk to policy makers is especially concerning.

The subsequent and ongoing reluctance of NZ authorities to publish any comparison of health outcomes for vaccinated and unvaccinated populations is hampering needs assessment. It is also withholding vital information from the public.

Misnaming an epigenetic intervention as a vaccine, as happened in the case of the mRNA vaccines, was a huge error driven by commercial considerations designed to improve public acceptance and drive sales. mRNA vaccines penetrate the cell membrane to act within the cell and modify its processes in a way that no other traditional vaccines have done in the past. This comprised a structural break with prior vaccination processes. It is no wonder that there has been a structural break initiating a rapid rise in the rate of incidence of mental illness coinciding with mass Covid vaccination.

What could be done to remediate the rise in mental illness?

A 2013 meta-analysis of the effects of deep meditation on trait anxiety reported meta-regression of 16 independent studies which found that initial anxiety level, but not other variables, predicted the magnitude of reduction in anxiety (p=0.00001). Populations with elevated initial anxiety levels in the 80th to 100th percentile range (e.g., patients with chronic anxiety, veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder, prison inmates) showed larger effects sizes, with anxiety levels reduced to the 53rd to 62nd percentile range. Studies using repeated measures showed substantial reductions in the first 2 weeks and sustained effects at 3 years. The results were highly statistically significant.

In fact, unqualified states of well being often referred to as transcendence are associated with extended neural networking. This has been estimated by measuring interhemispheric EEG phase and frequency coherence. In simple terms, experiences of universal or expanded consciousness are associated with the establishment of orderly brain networks over large regions via meditation. In contrast, violent and aggressive behaviour is associated with functional deficits in neural networks in the brain.

In the physiology there are many types of networks. Homeostatic networks aim to automatically maintain physiological parameters within limits consistent with health. The neural networks in the brain are information networks which can learn or grow with experience. Our genomic system is another type of network crucial to our identity. Every cell in our body has identical genetic material which as a whole supports our state of Being or in more common parlance our well being.

Experiences of expanded well-being are not exotic rare events accessible only to a few reclusive monks or yogis, nor do they require belief. Minimal instruction can be effective. In 1990 I was involved in the treatment of post traumatic stress at the invitation of the Armenian Ministry of Health following a massive earthquake in which over 25,000 people died. In all, 35,000 people participated in our deep meditation programmes which proved effective in remediating trauma.

The extent of vaccine injury relevant to mental health remains unknown and uninvestigated. More research is needed. Especially to understand how or if modification of genetic and epigenetic processes can be remediated. The treatment of mental illness whether it is caused by Long Covid or Covid vaccine injury may entail novel approaches on a scale never before attempted. In addition to the urgent need to tackle the cost of living, the housing crisis, employment, and training opportunities, combinations of methods including diet, herbal and mineral supplements, exercise, detox routines, breathing exercises, meditation, social and psychological support may be employed to alleviate our rapidly rising rates of mental illness before they escalate any further. We discussed some of these in our recent report “What Policies Could Improve Our Health Outcomes?“

It is probably too much to hope that governments will recognise the magnitude of the current mental crisis or realise that a range of approaches will be required to tackle it. In fact, our present parliament has consistently moved to impose a synthetic pharmacological approach on health measures. In particular, the Therapeutic Products Bill which has just been passed into law will restrict availability of natural approaches to health. This will undoubtedly restrict the ability of individuals to exercise self-help. As the pandemic crisis initiated by biotechnology experimentation continues to unfold, it is becoming more necessary for people to support one another in order to access solutions which lie outside of the narrow limits of current government health policy, some of which have exacerbated the problems.